CYPRESS HOUSE STYLE

CYPRESS HOUSE STYLE

Intro from Larry: “Wow. I started singing in a choir in 1957, when I was five (1st soprano). (photo) and I’ve never quit singing. I started “making-up” music when I was 14, on an accordion for puppet shows! – although it took ten years to realize how that crazy experience was an acorn. (biography) Swoooosh! Now, in my 70’s. having edited over fifteen-hundred scores for Cypress since 2010, I’ve formulated opinions, convictions, and proclivities that seem to work well for the Cypress look. With 12 years of post-secondary education – studying at the feet of luminaries and consulting with other publishing editors – I’ve arrived at a unique style for the company. Honestly, it’s a tremendous honour to work with over 275 fine Canadian composers, my peers, and I’ve learned lots from them. Many of the following details are neither right nor wrong, but please follow Cypress guidelines.

Less is More

Some scores are needlessly detailed. Cypress opts for “less is more” clarity, allowing for choir directors and piano players to make their own small musical interpretations. Composers need to trust choir directors. A choir pianist is often the most well trained musician in the group. Overly marked scores can come across as condescending – as if directors were not able to grasp the obvious. (e.g. when a soprano line divides into 2 parts, is it really necessary to add “divisi” or “div.”? What would the sopranos do if you didn’t add the obvious instruction? Would they say “What do we do now!!?” – (hahaha) Cypress tries to find a balance between the unnecessary and the helpful time savers.

Proof is in the pudding

While editing a score, Cypress listens to “rubber-meets-the-road” performances to see if the composer’s instructions were actualy being realized – or just wishful thinking. Then Cypress adjusts breathing and phrasing to emulate genuine performances. Composers are usually happy for such practical tweaks. Cypress webpages feature fine recordings which many singers listen to while practising their parts; so the audio and the score need to match closely.

Short story:

I’ll never forget having my first piece published – long ago. I was so excited. The typesetter happened to live close to my home so I gave him my score – which had LOTS of DETAILS, including phrase markings. He said, “Larry, sing this” – and I tried. Then he removed some of the markings – including the phrase markings and said, “Now sing this” – which I did. He didn’t need to say anything further. I realized that my overly persnickety-fastidious markings didn’t amount to a hill of beans. He concluded, “Trust directors and singers to be musical and don’t patronize them with needless markings.”

Redundancy

Is it really necessary to say “espressivo” or “cantabile”? Don’t all directors strive to have their choirs sing expressively? Do they really need reminding? Cantabile means “in a smooth singing style”. (hmm – singing in a singing style?) Doesn’t natural phrasing and word stress take care of that? Worse yet “Cantando” – a term which has informed directors running for the dictionary. In short, please avoid redundancy, nose-in-the-air terminology, and needless reminders about the obvious.

Tempo

Please do not use “ca” or “circa”. Unless the director is a living metronome, the tempo will be approximate anyway. Just state your ideal tempo and hope it turns out in the ball park vicinity.

The Tritone (devil’s interval) is a big no-no in any singing passage; unless applied the way Bach used it (as a leading tone in the bass line – from the 3rd to the tonic of the ensuing chord)

Intervals: remember that a singer needs to hear a note in his/her mind before singing it (unlike playing the piano). So a minor 6th needs to look like a 6th (not an augmented 5th) and a minor 3rd needs to look like a 3rd (not an augmented 2nd) – and so forth.

Voice leading is a Cypress specialty. It needs to be intuitive and approachable for average singers. Seemingly easy music can be difficult to sing and tune, depending on the horrible voice leading. Seemingly complex music can be easy to sing and tune – depending on the fine voice leading.

Oos and Ahs: watch this video, please.

Please avoid Cross Voicing – e.g. the altos singing below the tenors (unless you are trying to sustain a melodic passage)

There’s a reason why parallel fifths were once strictly forbidden; they are hard to tune! In fact, it takes experienced ears to tune a single sustained perfect fifth, which is slightly wider than a fifth on a well tuned piano. Parallel 2nds are a no-no. Be kind. Try singing “O Canada” with your friend a whole tone apart. Parallel octaves are a quick way to reveal pitch discrepancies between the two lines. Rudimentary voice leading rules help choirs to sound great. Please don’t be one of the composers who think “Now that I know the rules, I can break them at will.”

Breathing: Cypress adds breath marks and also specific rests (for breaths and articulation). If a breath requires a quarter beat, the notation should indicate precisely that – with a quarter rest. This saves all kinds of time during rehearsals! Words ending with consonants such as “t” or “d” need to be pronounced in unison (use a specific rest). Words ending in open vowels or consonants such as “m” are more forgiving – and a breath mark works fine.

Closed scoring (two staves – hymn-style voicing) is great for homophonic music – when all singers are singing the text in tandem. Open scoring (four staves) is essential for polyphony. It’s easy to switch back and forth (from closed to open) as necessary.

Rehearsal letters: Cypress uses double bar lines and rehearsal letters at significant musical moments, such as verses and choruses, key changes, tempo changes, etc. (this is designed to facilitate choir rehearsals).

Cypress slurs melismatic passages of text – according to the syllables. However, there is no need to slur long passages of “Oos” and “Ahs”.

The Font which is easiest to read? – Times Roman.

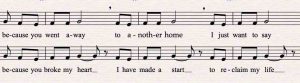

Hyphenation should be made according to the dictionary – not according to the way one might prefer to hear it. For example, imagine “another” sung on half notes per syllable”. One might be tempted to write “a – no – ther”, right? But the hyphenation is actually “an-oth-er”. One composer even hyphenated “Music” improperly – hahaha. A quick way to check? – simply google “define music”. Wouldn’t “Toxic” be hyphenated the same way as “Music”?

Divisi – e.g. SSAATTBB can look intimidating to directors of average choirs (most choirs). So, composers are asked to use them judiciously. It takes great skill to write a solid SATB composition (without divisi). Consider Mozart’s “Ave Verum Corpus” – perhaps the most exquisite “perfect” motet ever written.

Divisi – is it necessary to write “divi” when a vocal line splits into two or more parts? No – not at all – it’s obvious. The “divi” instruction makes sense for string players (to avoid double stops).

Expression – musical terms should be given in the universally accepted musical language; for example “adagio” rather than “slowly and calmly”. Cypress markets around the world and Japanese (for example) understand the traditional terms. Use the most common terms: Ritardando (Rit.) instead of Rallentando (Rall.)

Expression (part 2) – avoid using needlessly persnickety terms such as “like a falling feather” – especially in English. Affectations such as “like a bubbling brook” just raise questions marks and slow down the rehearsal. How about “like the wind”? – this could result in a breathy tone quality – like Monroe’s “Happy birthday, Mr. President”. – hahaha

Fortes should never be louder than beautiful unless the composer intends to convey anger. One composer sent us a piece with a quadruple forte ( ffff), which means really, really, REALLY loud. Just “loud” should be adequate. So double fortes are rarely found in a Cypress score.

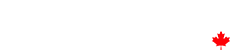

Syncopated passages – the importance of beaming. Average singers need to see beats 3 and 4. (beats 1 and 2 are readily apparent) Click here for an explanation.

Piano parts need to look tidy without too many slurs, phrase marking, hairpin dynamics, etc Pedalling is largely left to the pianists’ discretion – rather than cluttering up the score with pedal on and off markings. Occasionally very specific directions are relevant at certain points in the score. However, “pedal freely” or “pedal with harmonic changes” usually work for a competent piano player and they love the freedom to be musicians.

Reminder Accidentals – while we understand that a bar-line cancels earlier accidentals, reminder accidentals can really add clarity for singers and accompanists.

Contrapuntal a cappella scores should have a piano reduction so the piano player can assist with rehearsals.

Piano reductions for a cappella scores should be “bare bones” without slurs, tempo markings or dynamics.

sub mp? or mp sub? – debatable for sure (see the argument online), but what does a player need to see first? If one is singing forte and it suddenly changes to pianissimo does one really need to be told that it is “suddenly”? “Subito” is only a reminder of the obvious and what a player/singer needs to see first is the dynamic itself.

Mixing sharps and flats in the same passage is generally confusing and not wise. For singers a minor 3rd needs to look like a 3rd and not an augmented 2nd. (For example F up to Ab is more intuitive – easier to navigate – than F up to G#.)

Dynamic hairpins should usually have a beginning and ending dynamic marking. (rather than leaving the director pondering questions such as “crescendo to what? – how much louder?”). However, “swells” over a short passage are generally understood without other dynamic indicators.

“Floating like a feather on the summer wind?” “Jagged like mountain peaks?” How about “legato” and “marcato”? Please use terminology that is universal. Avoid flowery descriptions that cause discussions/arguments and just waste rehearsal time.Choirs want to realize a composer’s intentions but please have mercy!

Dynamic markings – Please stick with the tried and true traditional markings. Examples: fm+, fm-, pseudo pp, poco mp, più mf, These are affectations which mean little to singers and only frustrate the process. Wouldn’t an mp+ sound much like an mf – ? – and how would one measure that? – with a decibel meter? What if the choir is 12 singers – or 75 singers? Trust the director and trust the singers to shape your intentions with a healthy dose of their own passion.

Fermatas are vague. Hold? – for how long? Leave it up to the director.

Dotted slurs indicate “carry the phrase without a breath”. Breath mark indications can really help expedite a rehearsal. Use them.

6/8 or 9/8 time; we used dotted quarter rests because they communicate better than a whole rest for an entire bar. A whole rest in a 6/8 bar looks like 4 counts to some singers. Two dotted quarter rests would be a user-friendly option.

Note stems for divisi on one staff can go in opposite directions or in the same direction depending on formatting needs and legibility – and it’s not crucial to be consistent.

“Thru” instead of “Through”? “Thru” is in the dictionary too and Cypress doesn’t hesitate to use it in order to avoid word crowding and achieve attractive spacing. “Through” might work on a whole note or half note but perhaps not within an eighth note passage.